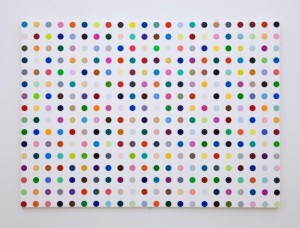

Damien Hirst Spot Painting

There is an abandoned building near Iroquois Ontario that says, “I love Christine Kirkwood by Cole”. Sometimes it’s difficult to know what’s important, but this message has stayed with me like poetry. Christine Kirkwood sounds very beautiful and I think Cole uses all of Christine’s name so he can call up her complete and perfect idea. If he knew her middle initial, that would be part of the conjuring as well – Christine J. Kirkwood. Their relationship does not seem equal to me, just like their names. Christine Kirkwood probably does not love Cole. She may not even like him, or for that matter, know who he is.

I also find the word, “by” in “I love Christine Kirkwood by Cole” very significant. It is definitely childlike, but it also reveals an important truth. “I love Christine Kirkwood” is the title of a greater work by Cole, not just a simple statement of fact. Our feelings involve the whole of us, all of our bodies, including our nasal passages and bowels, and no matter how sophisticated we become, we can never produce an expression that equals a state of our selves. Loving Christine Kirkwood is so much more than can ever be said. We remain alone with our secrets and yearnings except when they are unintentionally revealed to a steadfast interpreter.

Artists are like Cole in that intentional self-expression may not be possible. Self-portraiture, on the other hand, certainly is possible. Whenever someone makes something, that artefact is accompanied by an imaginary someone who is plausible as the person who made that something. This is not the artist – this is an image of the artist in the mind of the viewer. The writer-person who you are starting to imagine as you read my words is a good example of a plausible imaginary someone. My thoughts on Cole are also an example.

Artists can manipulate this image of themselves to help them appear clever, or innovative, or whatever it is they want for themselves. But it is difficult to be a perfect manipulator. It follows from this that the image of the artist that becomes apparent in a work of art is only partially intentional on the artist’s part, while the rest, that being the artist-desired part, is unintentional or perhaps even an error or oversight depending on the artist’s mendacity. Friedrich Nietzsche says that reading a philosopher’s works uncovers the character or moral health of that philosopher. I am saying something similar about art and artists. If my claim holds, it could be a great boon to the hermeneutics industry.

Paul Klee, Ancient Sound, oil on cardboard, 15″ x 15″, 1925, coll. Kunstsammlung, Basel. http://www.sai.msu.su/wm/paint/auth/klee/

The thought of ancient sound is truly delightful and reminds me of some lines from a poem by Hans Arp, “No one detects now the track of his baby shoes. They left not even a threadlike trace of a tiny hiking-song in the air.” [Hans Arp, “The Seraphim and Cherubim” in Three Painter Poets: Arp, Schwitters, Klee, Harriet Watts trans., Penguin Books, 1974, p. 32]

The self-portrait that Klee is showing me is a playful, modest person who takes great pleasure in poignancy. My imaginary Klee has charmed me. It’s also a beautiful painting.

Sometimes a painter paints in a particular way just to make a painting that is painted in that particular way. These kinds of paintings are meant to look just as they look. This is a very straightforward kind of painting, and it makes a much better door than window. In other words, the painting that is right in front of me is the thing intended to be seen, and the painting is not meant to be seen through to something else such as a talented imaginary artist.

It is very nice that some straightforward, door-like paintings are about the paint itself, or the support for that paint (formal concerns), but it is much more interesting when straightforward paintings are also about something else as well, this often referred to as “content”. But content contains an unfortunate metaphor – content is not inside a painting, content is the painting perceived.

This is why a straightforward painting, even when it is about something else as well, ancient sound as an example, still makes a better door than window. The painting is the thing to be seen, not an imaginary painter or an alienated context such as “the history of art such that this painting is a part of it”, “the history of art such that this painting is a clean break with it” or “an appropriate stance on a burning issue of the day”. These latter kinds of paintings are conceptual paintings.

A conceptual painting is thus an object that is presented as if it were a painting. Some fancy people might call this a simulacrum, but I believe these two things are different. Unfortunately, I don’t find it worth the time just now to clarify that distinction. Thus, a stretched canvas that has had paint applied to it by a human and then been hung on a wall could well not be a painting at all. Fun.

Conceptual painting is not straightforward – it is painting that is presented as painting in order to make a point about something unrelated that is not there to be seen in the painting itself. It might be something like, “The person who made this painting has a new and better understanding of some particular strand in the history of art up to and including this painting here which is making this very point”.

It will be up to the viewer/interpreter to figure out what that understanding might be. An official artist’s statement can be of great value in this regard. The long tradition of the artist’s manifesto has evolved into a standard business letter document to help viewers negotiate these conceptual issues. Most contemporary artists are wary of the artist’s statement. To keep their inscrutability intact, it is better to leave this to their gallery representatives and the critics who write articles about them.

Conceptual painting of course, is a wonderfully clever thing to do, and it makes the painter an art historian and theorist worthy of respect. It also makes the conceptual painter not a painter at all and the conceptual painting not a painting, in spite of the fact it looks like one.

In my opinion, Damien Hirst’s spot paintings are fine examples of conceptual paintings. There is nothing to be gained by merely looking at them, just like all conceptual art, knowing about them is sufficient. There’s more on this in my preface to The Communist Manifesto without Nouns.

I think the spot paintings are primarily about how art is a kind of money, which is not a terribly novel idea – the idea of the cultural commodity has been nagging the conscience of artists for quite a while. Oscar Wilde said that a philistine knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. This comment may or may not be applicable to this discussion, although I suspect it is. I feel confident that Hirst’s Spot Paintings are conceptual paintings with a debt to Warhol, and they therefore they have nothing to do with spots.

Georges Seurat, Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp, 1885.

Seurat, on the other hand, was very interested in spots.

.

Steve Armstrong, Satie’s Column, 6.5″ x 9.5″ x 58″, acrylic on wood, 1997.

Steve Armstrong, Schoenberg’s Column, acrylic on wood, 7″ x 10″ x 94″, 1994.

I find spots interesting as well.

.

And Robert Fones also sees something interesting in spots and dots..

http://archives.chbooks.com/online_books/head_paintings/wonder_bread.html

Here’s Fones from the Coach House books site:

WONDER BREAD

I have always liked the simplicity of the six dots in the Wonder Bread logo and its evocation, in product design, of Modernist principles. I remember seeing the logo as a child and associating it with one of my favourite comic book characters, Little Dot, a girl who was obsessed with dots and collected them the way other people might collect coins or butterflies. To construct this painting I found a Wonder Bread logo on the side of a truck and photographed it in order to find out how many different sizes of dots there were, and how the dots were arranged. As with Pancetta, once I positioned an altered configuration of dots on the face, I extended them back in perspective as if they were solid material. I thought of the eyes and tongue as planes of material cutting through the solid logo, hence whatever colour they sliced through was carried forward or backward in pictorial space. The head ended up looking clown-like but rather tragic, as if it was unaware of the dots on its face.

I see more in Fones’ piece than he mentioned. He mostly described the imaginative play that artists enjoy so much, “I extended them [the dots] back in perspective as if they were a solid material”. Fones’ playful attitude towards his work seems similar to that of Paul Klee. But besides this, I see a metaphor for perception. The spots to be perceived by the face are on the outer surface of that face, and they leak in through its sense organ holes. It says to me that the things I perceive are not “over there”, I am actually touched by everything. There is no empty space between me and the things I experience. On my part of course, this is just more of that imaginative play that artists enjoy so much. It’s also worth noting that Klee’s “Ancient Sound” is also a reference to perception.

And to get back to Seurat, he was a very earnest fellow researching the limits of the relationship between granularity and continuousness as it applies to perception. There might be a reason why spots and dots seem to lend themselves so well to meditations on perception. Henri Bergson published Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness in 1910 which also considers the issues of the discrete versus the continuous. It was based on his doctoral dissertation of 1889. For what it’s worth, this was contemporary with Seurat.

As an aside, Seurat also made absolutely superb pencil drawings. I love them very much.

Georges Seurat, Aman–Jean, conté crayon on paper; 24 1/2″ x 18 11/16″, (62.2 x 47.5 cm) 1883. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/61.101.16

Discussion Points for ISTP Novices, Fledglings, and Supplicants

Was Hirst’s character impugned?

Was this text theoretical, or anti-theoretical, or both?

Is there any urgency to understanding the distinction between a simulacrum and something that is regarded as if it were something else?

Image at top: Damien Hirst Spot Painting from http://www.pasunautre.com/2011/12/28/art-in-2012/

Very creatively written. I love what these colors do to my retinas also. Lol :-))

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

Hirst’s character was not impugned, thank you.

The text did not seem to take a position on theory, nor was it theoretical.

The distinction you wiggle your fingers over is worth a closer look, but not urgently. In any case, it’s theoretical

LikeLike

I received a comment through LinkedIn that seems to imply that Hirst’s character was impugned. She also made a valid point that prompts me to confess overstepping the bounds of fairness. I’ve never seen any of his spot paintings except online or in magazines, thus it is possible that there might be something to be gained by merely looking at them. Nonetheless, I doubt it. I should also say that I believe his work has merit although it is not as important as Warhol’s.

I agree with you about Hirst, but I had a lot of fun insinuating things. Sadly, I think he might be going down Michael Jackson’s road.

Theory is a great hobby for artists, but it’s just a hobby.

LikeLike

and i enjoyed reading it very much, and that is a practical matter

LikeLike

Beautiful. Love the baby footprints. From Rumi’s Song of Reality:

“I am not from the East or the West, not out of the ocean or up from the ground,

not natural or ethereal, not composed of elements at all. I do not exist,

am not an entity in this world or in the next, did not descend from Adam and Eve or any

origin story. My place is placeless, a trace of the traceless. Neither body or soul.”

These words from Rumi (translation) seem to also be closely connected to your striking comment, “….content is the painting perceived.”

I’d like you to present a work of art of your choice, straightforward art, as a vehicle for people to write out what is perceived. It could be interesting to compare/contrast the perception of the viewers who choose to describe their perception. It might be more difficult for artists to do this. Original perception is clouded by concepts.

Let’s animal out on a painting.

LikeLike

Wow, what a challenge. Interestingly, I have an early draft post about a painting called The Descent of Geometry that proposes many interpretations. That might be the one.

Arp’s lines about baby shoes are marvellous. They tell me that wistfulness and nostalgia are negative emotions. They also explain the beauty of poignancy. Mozart does that for me too.

I’ve read a lot of Rumi, but I didn’t connect the dots on that one. It’s an idea so simple, it’s easily baffling. It requires experience. You’ve made me very proud of my little sentence. I’m considering ” Content is the painting perceived” for my tombstone.

LikeLike

Steve, I loved this post. As usual I had to read it twice and then skip through it again. Not because it is confusing but because it is incredibly rich. It is like the door you refer to and as you point out, you need to go through to see what is really there.

As you know, I’m find joy in mathematics and related stuff. I once was at a party full of arts undergraduates where I admitted as much. One person had a physical reaction of disgust. I had quite a short evening there and it left me disappointed, and not just on this person’s social skills.

The thing is that behind my door of mathematics, I am an artist. And it took me decades to admit that, with shy pride. We, the artists in maths clothing use a different language (mathematics) that is unfortunately hard to penetrate. We observe our world and comment on it, using a handful of symbols. That canvas of symbols is like your dots; unless you look through them, you’ll only see ugly or beautiful things and you can stop there. But what about deeper story? What does it say about the person who wrote this?

When Albert Einstein wrote E=mc2 he didn’t just write a solution to a problem. It was also a pen and ink sketch of the universe. It was an expression of his deepest thoughts about a world he lived in. It said something about his relationships with his contemporaries.

Conceptual Art as self expression. Maths as self expression. Maths as Conceptual Art.

I love contemporary art even if I don’t understand a lot of it. I love the pieces you show here, including your own art. I read different things in it but it silences me and makes me contemplate deeply: who is this person?

Sometimes I wish I could take others into my world of maths and show them the art that is there.

Sometimes I do.

Mind you, it isn’t all art in maths. Some of it lacks imagination, is boring and pointless. But even then, like the elements in a commercial flier, there are inspiring traces that leads to nerds that paint in secret or play the congas when no one is listening.

Thanks for making me think and appreciate. Henk.

LikeLike

I know a number of artists, including myself who think of mathematicians and physicists as kindred spirits. Knowledge and beauty dance together for all of us. I wish I were less illiterate with math. Infinitesimals in calculus are fascinating, as are transfinite numbers. And being a very visual person, the golden section won’t let me go.

LikeLike

If I look at the dotted columns I cannot get the thought of that building (or was it a whole street?) in New Orleans out of my mind: Where visitors attach their colored chewing gums to the building so that the lower part of it looks as painted in dots. Not sure if this says something about me or about artwork using points(?)

LikeLike

I’d love to see that building. Years ago there was an abandoned building in Hamilton, Ontario with hundreds of pop and beer cans nailed on it. What’s not to like about that? My columns look like skyscrapers to me too.

LikeLike

[…] An addendum to Self Expression and Conceptual Painting. […]

LikeLike

[…] time for a third voice to consider the issues raised in Self Expression and Conceptual Painting and Repressed Anger. The former was a sincere attempt to understand beauty, the latter, an attempt […]

LikeLike